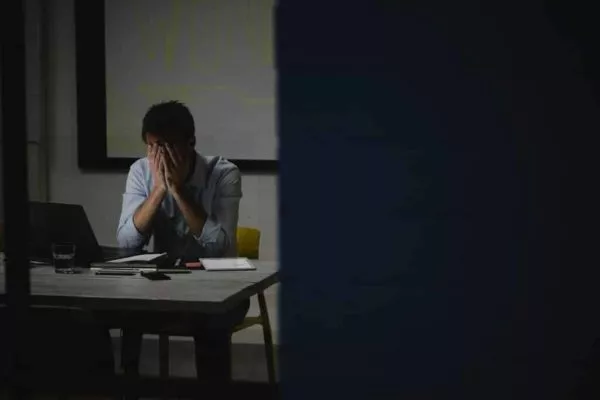

Have you ever felt nervous or afraid to take time off from work to look after your mental health?

Marisa Kabas, a writer and political strategist who lives in New York City, recently posed a similar question on Twitter, inspired by Simone Biles, who bowed out of Olympic events this week to protect her mental health.

“It was so shocking to so many people,” Ms. Kabas said on Wednesday in an interview. “Because the whole mentality is be strong, and push through the pain.”

The tweet drew thousands of responses, many from employees who said they do not disclose the real reason they need time away from work, or feel pressured to lie about it because they are embarrassed. Others said they had never taken a mental health day.

As a freelancer who has written prolifically about her health problems, including anxiety and depression, Ms. Kabas said she sometimes wakes up and decides, “I can’t do it today,” and takes the day off, a luxury she didn’t feel she had as an employee.

About three-quarters of people in the United States who work for private industry, state or local government have paid sick leave, but surveys suggest that a number of these employees are unlikely to use sick days for mental health reasons or are scared of being punished for doing so.

If you’re among the hesitant, experts say it’s time to start thinking about how to protect and prioritize your mental well-being, especially as millions of employees who worked remotely during the pandemic start returning to the office.

“You wouldn’t feel bad about taking time off when sick. You shouldn’t feel bad about taking some time off when you’re sad,” said Natalie C. Dattilo, a clinical health psychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and an instructor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “Your body needs a rest, your brain needs a break.”

How do you know if you need a ‘sad day’?

There’s no official definition for a “sad day,” also known as a mental health day. Typically, it is paid time off drawn from sick days (or personal days) to help employees who aren’t feeling like their usual selves, offering an opportunity to refresh their minds; do something meaningful; or simply take a break from daily stressors. The “sad day” is only a temporary fix, and not meant to address deeper problems, but sometimes a little time away can make a big difference.

Your company may not specify that sick days can be used for this purpose, but “mental health is health,” said Schroeder Stribling, the president and chief executive of the advocacy group Mental Health America. “The two are inseparable.”

The signs that you need to take time away from work may not necessarily be obvious, Ms. Stribling said. Indicators include changes in your mood, productivity or ability to concentrate. You may also notice that you are less patient and more irritable than usual, or are having trouble sleeping.

You might also have physical symptoms. For example, “if I start getting headaches, that’s a sign of stress for me, and I need to address that with a mental heath day,” Ms. Stribling said.

The bottom line: Given the extraordinary stressors of the last year and a half, regardless of your specific symptoms, “if you feel like you might benefit from a mental health day, you have earned one,” said Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton business school, whose recent podcast explored the benefits of the “sad day” and the importance of building a culture of compassion within the workplace.

Some companies may require employees to provide documentation, such as a doctor’s note, when they use sick days, so make sure you understand what the law says in your region. In New York City, for example, an employee is not required to provide documentation unless more than three consecutive days of sick leave have been used.

How do you ask for a mental health day?

Your workplace culture and your relationship with your manager will dictate how open you choose to be about why you’re taking time off. You should not feel compelled to divulge more than necessary.

“I think sometimes we over-share when we’re anxious or perhaps feel a little bad about having to take time,” Dr. Dattilo said.

In most situations, just say that you need to take a sick day, and leave it at that, the experts advised.

“I think the safe advice is not to be upfront,” said Andrew Kuller, a clinical psychologist at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. Not everybody values mental health, he added, and “unless you’re close with your supervisor, it is a risk.”

But say you work at the type of organization where you can tell the truth without fear of being punished. In that case, you are still under no obligation to reveal why you want to take a sick day. However, if you want to share (or are interested in reducing some of the stigma around mental health) you might approach your manager and say, “I think I would really benefit from taking a day just to recharge a little bit,” Dr. Grant said. “I would like to come back to work with all of my energy.”

When employees are mentally and physically exhausted, it affects the quality of their work, their productivity and the people around them, Dr. Grant added.

“I think it’s easier to have a conversation about burnout than it is about feeling sad or depressed or anxious, so I would probably play it safe there, and highlight why this is good for the organization, not just good for you,” he said.

If you’re feeling up to it, you can also try to assemble a coalition of people within your department who are concerned about mental health fatigue, said Dr. Grant, whose latest book, “Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know,” challenges readers to shift long-held thought patterns. As a group, you can discuss concerns like missed deadlines or errors that might be compounded by burnout, then bring these issues to your manager, who may be motivated to find a solution. That way, you can try to change the system for everyone, including yourself.

Click here to read the full article on the New York Times.