By Martin Anderson, Unite

Researchers from Germany have developed a method for identifying mental disorders based on facial expressions interpreted by computer vision.

The new approach can not only distinguish between unaffected and affected subjects, but can also correctly distinguish depression from schizophrenia, as well as the degree to which the patient is currently affected by the disease.

The researchers have provided a composite image that represents the control group for their tests (on the left in the image below) and the patients who are suffering from mental disorders (right). The identities of multiple people are blended in the representations, and neither image depicts a particular individual:

Individuals with affective disorders tend to have raised eyebrows, leaden gazes, swollen faces and hang-dog mouth expressions. To protect patient privacy, these composite images are the only ones made available in support of the new work.

Until now, facial affect recognition has been primarily used as a potential tool for basic diagnosis. The new approach, instead, offers a possible method to evaluate patient progress throughout treatment, or else (potentially, though the paper does not suggest it) in their own domestic environment for outpatient monitoring.

The paper states*:

‘Going beyond machine diagnosis of depression in affective computing, which has been developed in previous studies, we show that the measurable affective state estimated by means of computer vision contains far more information than the pure categorical classification.’

The researchers have dubbed this technique Opto Electronic Encephalography (OEG), a completely passive method of inferring mental state by facial image analysis instead of topical sensors or ray-based medical imaging technologies.

The authors conclude that OEG could potentially be not just a mere secondary aide to diagnosis and treatment, but, in the long term, a potential replacement for certain evaluative parts of the treatment pipeline, and one that could cut down on the time necessary for patient monitoring and initial diagnosis. They note:

‘Overall, the results predicted by the machine show better correlations compared to the pure clinical observer rating based questionnaires and are also objective. The relatively short measurement period of a few minutes for the computer vision approaches is also noteworthy, whereas hours are sometimes required for the clinical interviews.’

However, the authors are keen to emphasize that patient care in this field is a multi-modal pursuit, with many other indicators of patient state to be considered than just their facial expressions, and that it is too early to consider that such a system could entirely substitute traditional approaches to mental disorders. Nonetheless, they consider OEG a promising adjunct technology, particularly as a method to grade the effects of pharmaceutical treatment in a patient’s prescribed regime.

The paper is titled The Face of Affective Disorders, and comes from eight researchers across a broad range of institutions from the private and public medical research sector.

Data

(The new paper deals mostly with the various theories and methods that are currently popular in patient diagnosis of mental disorders, with less attention than is usual to the actual technologies and processes used in the tests and various experiments)

Data-gathering took place at University Hospital at Aachen, with 100 gender-balanced patients and a control group of 50 non-affected people. The patients included 35 sufferers from schizophrenia and 65 people suffering from depression.

For the patient portion of the test group, initial measurements were taken at the time of first hospitalization, and the second prior to their discharge from hospital, spanning an average interval of 12 weeks. The control group participants were recruited arbitrarily from the local population, with their own induction and ‘discharge’ mirroring that of the actual patients.

In effect, the most important ‘ground truth’ for such an experiment must be diagnoses obtained by approved and standard methods, and this was the case for the OEG trials.

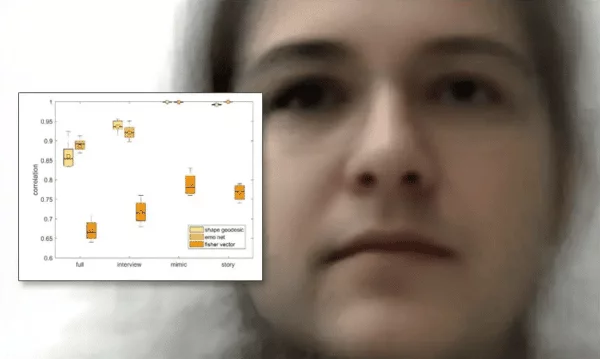

However, the data-gathering stage obtained additional data more suited for machine interpretation: interviews averaging 90 minutes were captured over three phases with a Logitech c270 consumer webcam running at 25fps.

The first session comprised of a standard Hamilton interview (based on research originated around 1960), such as would normally be given on admission. In the second phase, unusually, the patients (and their counterparts in the control group) were shown videos of a series of facial expressions, and asked to mimic each of these, while stating their own estimation of their mental condition at that time, including emotional state and intensity. This phase lasted around ten minutes.

In the third and final phase, the participants were shown 96 videos of actors, lasting just over ten seconds each, apparently recounting intense emotional experiences. The participants were then asked to evaluate the emotion and intensity represented in the videos, as well as their own corresponding feelings. This phase lasted around 15 minutes.

Click here to read the full article on Unite.